Coccidioidomycosis and aspergillosis in a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis sequelae

Flores-Acosta, Rogelio1; Félix-Ponce, Miroslava1; Jiménez-Gracia, Alejandra Isabel1; Laniado-Laborín, Rafael1,2

Flores-Acosta, Rogelio1; Félix-Ponce, Miroslava1; Jiménez-Gracia, Alejandra Isabel1; Laniado-Laborín, Rafael1,2

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS

coccidioidomycosis, aspergillosis, tuberculosis, sequelae.Introduction

Pulmonary tuberculosis is the most frequent cause of pulmonary cavities1 and is recognized as a predisposing factor for colonization by Aspergillus spp., a severe and life-threatening complication.2 However, pulmonary coccidioidomycosis can present similar clinical and radiographic patterns, especially in immunocompromised patients.3

This report describes a case of coexistence of Coccidioides spp. and Aspergillus spp. in a patient with a history of diabetes mellitus and fibrocavitary sequelae from pulmonary tuberculosis, highlighting the relevance of comorbidity due to endemic or opportunistic mycoses in immunocompromised patients.

Clinical case

48-year-old Mexican woman, diabetic with poor metabolic control (central glycemia 265 mg/dL); two years earlier, she was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis receiving treatment and discharged as cured.

She developed night sweats, cough, hemoptysis, and weight loss one year later. Her sputum smear microscopies are reported negative for acid-fast bacilli, so she is referred to the Tuberculosis Clinic at the Tijuana General Hospital for tuberculosis molecular and phenotypic diagnostic tests. Smear microscopy, Xpert® MTB/RIF test (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA), and cultures (MGIT® BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ, and Lowenstein Jensen) are reported negative for tuberculosis.

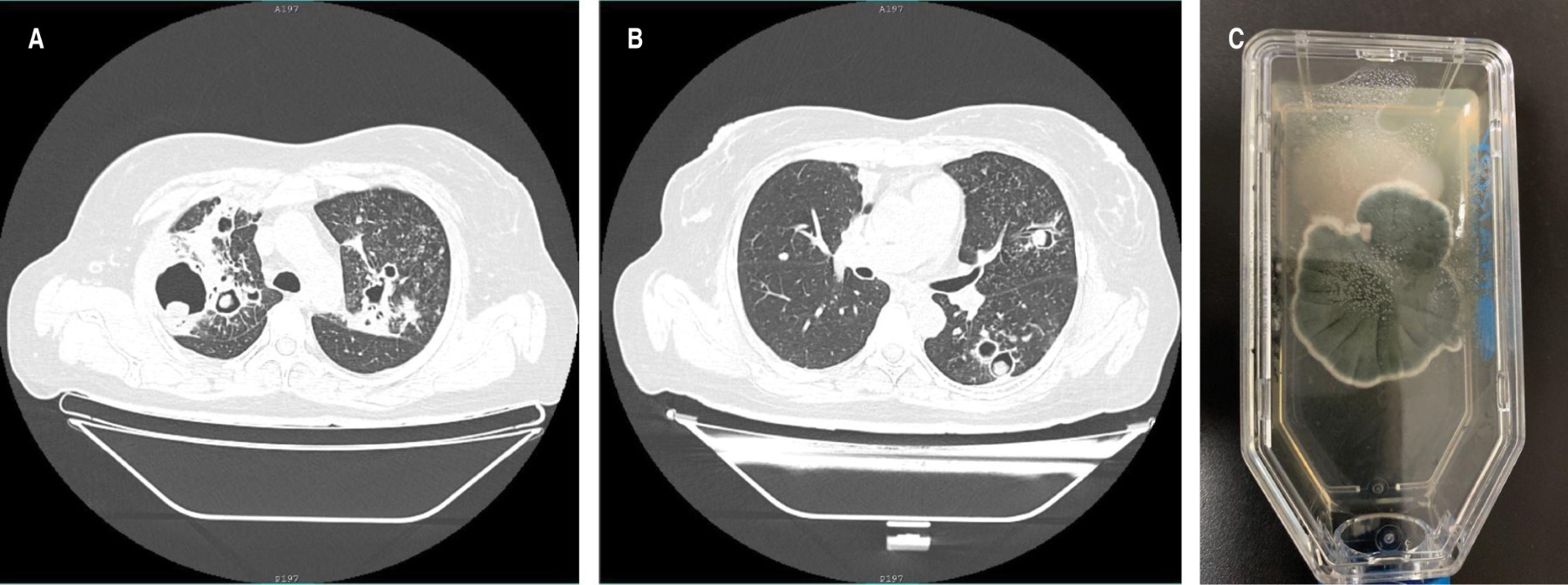

The chest radiograph showed multiple bilateral thin-walled cavities, with an intracavitary mass in several of them. Chest computed tomography (Figure 1A and 1B) confirmed the findings and allowed the identification of a greater number of cavities with an intracavitary mass.

Sputum fungal culture showed the simultaneous isolation of Coccidioides spp. and Aspergillus spp. (Figure 1C). The hospital unit does not have access to serology tests for these mycoses. She was started with itraconazole 300 mg every 12 hours, showing clinical improvement after a month of treatment.

Discussion

The search in PubMed, Google Scholar, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library did not yield reports on the simultaneous presence of Coccidioides spp. and Aspergillus spp. in patients with fibrocavitary sequelae of tuberculosis.

Residual lung damage even after successful treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis includes fibrocavitary lesions, bronchovascular distortion, emphysema, and bronchiectasis.4

The main risk factors that favor disease by these mycoses are a history of structural lung damage and immunocompromise. In our patient, residing in an endemic area of tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis and being immunocompromised due to diabetes with poor metabolic control,5 were the predisposing factors that favored the concomitant development of these mycoses.6-8

The patient was referred to the tuberculosis clinic, suspecting a tuberculosis relapse. However, based on the negative results of the phenotypic and genotypic tests for tuberculosis and the presence of multiple cavitations with an intracavitary mass, fungal sputum cultures were requested, suspecting colonization by Aspergillus spp., which was indeed detected, reporting in addition, the unsuspected presence of Coccidioides spp.

Coccidioidomycosis is exclusive to the American continent, being endemic in the southwestern United States and northwestern Mexico,9,10 where our patient lives. Aspergillosis is an opportunistic mycosis caused by the saprophytic soil fungus Aspergillus spp., with Aspergillus fumigatus the most frequently identified species.11

The culture of respiratory samples is the study of choice for the diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis.9

Serologic tests identifying anticoccidial humoral antibodies (IgM and IgG) are an alternative method (and the most frequently used) for the diagnosis and prognosis of coccidioidomycosis.10

Aspergillosis has different clinical presentations, which frequently overlap. Chronic cavitary aspergillosis (CPA) usually shows multiple cavities that may or may not contain an aspergilloma, in association with pulmonary and systemic symptoms, as well as elevated inflammatory markers. Without treatment, these cavities increase in diameter and coalesce, developing pericavitary infiltrates, which a bronchopleural fistula can complicate.12

The diagnosis of CPA requires a combination of different criteria: a consistent appearance on radiological images, direct evidence of Aspergillus infection, an immune response to the fungus, and the exclusion of an alternative diagnosis. Patients with CPA are not usually immunosuppressed by HIV infection, chemotherapy, or immunosuppressive therapy.12 Proven diagnosis of aspergillosis requires histopathological documentation of the infection, or a positive culture result from a sample taken from a sterile site.11 Additionally, the detection of galactomannan (GM) in plasma should support the diagnosis of aspergillosis.13 In our case, isolation of Aspergillus was from a non-sterile sample, and it must be classified as probable aspergillosis infection based on the predisposing factors, suggestive clinical and tomographic data, and mycological evidence.7,8

The presence of Coccidioides spherules in respiratory samples always represents disease, while the presence of Aspergillus can be associated with disease or colonization.12,14

Conclusions

In patients with tuberculosis sequelae with respiratory symptoms, tuberculosis relapse should be initially ruled out, and opportunistic and endemic fungi such as Aspergillus spp. and Coccidioides spp. should be considered in the differential diagnosis algorithm.

AFILIACIONES

1 School of Medicine, Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico, Tuberculosis Clinic, Tijuana General Hospital, Mexico. 2 School of Medicine, Autonomous University of Baja California, Mexico, Tuberculosis Clinic, Tijuana General Hospital, Mexico, SNI II, CONACYT.Conflict of interest: the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this publication.

REFERENCES

Avilés Robles MJ, Mendoza Camargo FO, Romero Baizabal BL, Serrano Bello CA, Ortega Riosvelasco F. Aspergilosis diseminada por Aspergillus flavus en un paciente pediátrico con leucemia linfoblástica aguda de reciente diagnóstico. Bol Med Hosp Infant Mex. 2017;74(5):370-381. Disponible en: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmhimx.2017.05.003

Donnelly JP, Chen SC, Kauffman CA, Steinbach WJ, Baddley JW, Verweij PE, et al. Revision and update of the consensus definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for research and treatment of cancer and the mycoses study group education and research consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(6):1367-1376. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1008.